At a press conference to announce that the European Central Bank was lowering interest rates, ECB president Christine Lagarde quoted the song “Que sera sera,” made famous by Doris Day in The Man Who Knew Too Much. This made me think of the culinary demonstrations known in Spain as “show cookings.” I’ll explain.

What caught my attention about Lagarde’s quip is that she didn’t actually reference the song, or Doris Day, but rather said “I am tempted to quote the Spanish, que sera sera,” making it clear that she, like many people, are belaboring under the impression that this is a common saying in Spanish. It’s not. In fact, it’s not even grammatical in Spanish. The grammatical equivalent would be “Lo que será, será,” but while this is sayable, it’s not exactly something any Spanish speakers would recognize as a saying. A more idiomatic expression to convey this throw-up-your-hands kind of attitude to the future would perhaps be “Que sea lo que Dios quiera,” which literally means “May it be whatever God wants,” but is used rather loosely and without any particular religious fervor in most cases. But I digress.

I couldn’t help wondering if the press conference had simultaneous interpretation into Spanish and, if so, how the phrase in question was rendered by the Spanish interpreter, given the rather awkward state of affairs of having to translate into your language a phrase that supposedly comes from your language. It’s a situation I’m familiar with, given the proliferation of pseudo-anglicisms in contemporary Spanish, especially peninsular Spanish. In many cases, such as the notorious example of “footing,” (the activity actually known in the English-speaking world as “jogging”) these words are so obviously not actual English that no translator will be fooled by them. However, there are more subtle pseudo-anglicisms that often do trip up translators. Here are just a few of them.

Performance: A staging of Hamlet, a violin concerto, and a contemporary dance show could all be described as a “performance” in English. But the pseudo-anglicism “performance” is typically used to refer to a specific kind of interactive and avant-garde artistic creation better known as “performance art” in English. Indeed, the RAE defines it as “Actividad artística que tiene como principio básico la improvisación y el contacto directo con el espectador,” in an entry that tellingly doesn’t include words such as “función” or “representación” that one might use when translating “performance” from English into Spanish. Though the DIEC doesn’t yet include “performance,” Termcat defines it as a “Manifestació artística de caràcter multidisciplinari en què l’autor, present físicament o no, busca impressionar vivament el públic, desenvolupada especialment a partir del final dels anys cinquanta del segle xx” and lists both “performance” and “performance art” as the English equivalents. Meanwhile, Cambridge defines “performance” (in the relevant context) as “the action of entertaining other people by dancing, singing, acting, or playing music,” clearly a much broader concept than the Spanish or Catalan definitions.

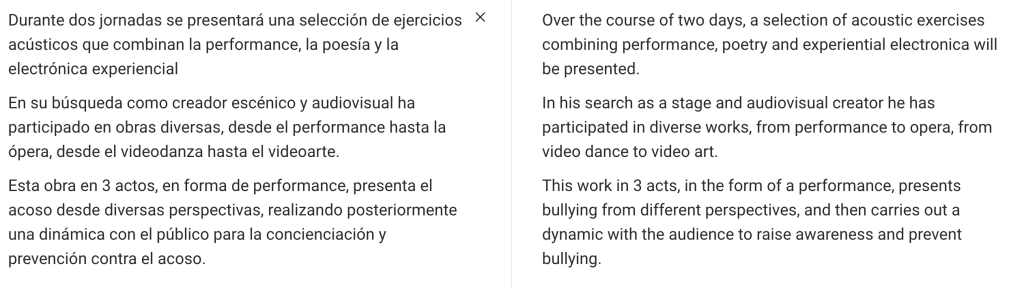

Nonetheless, unlike with other pseudo-anglicisms such as “rider” to refer to delivery workers, a context in which English would never use the word, there is enough semantic overlap between “performance” and “performance art” to confuse even a careful translator. In fact, bilingual dictionaries such as Collins give “performance” as the English translation of Spanish “performance”, and relatively good MT engines don’t usually pick up on the difference, either, as I saw for myself when I tried putting three sentences (originals found here, here, and here) through DeepL. Since you never step in the same machine translation engine twice, and DeepL in particular is rapidly improving, it’s possible that the same exercise a few months from now will offer different results, but as of February 2025 the machine, just like Collins and many human translators, seems to be operating under the assumption that the two “performances” are synonymous:

The oddity of phrases such as “from performance to opera” in English, where opera would typically be considered a kind of performance, is further proof that the words are not used in the same way in the two languages. Though the awkwardness is just subtle enough that it often goes unnoticed, stepping back and recognizing that this is actually “performance art” makes all the difference in successfully explaining the concept to an English-language audience.

It should be noted that “performance” has also taken on meanings that have little to do with the world of entertainment. Performance art isn’t exactly everyone’s cup of tea, and perhaps that’s why “performance” has also become a disdainful way of referring to showy initiatives that may or may not have artistic intentions. In this context, it can be translated as “gimmick” or a “shtick” or recast in a way that involves the word “performative,” a dismissive way of referring to a way of acting that is perceived as insincere.

Show cooking: The problem with this psuedo-anglicism is different. While any native English speaker knows that this is simply not a term used in English, it’s not immediately obvious how it should be translated. Like many into-English linguists, I once assumed that this was simply an odd way of referring to “cooking shows,” most likely coined by someone who didn’t have a great grasp on English syntax. When I learned more about what the concept actually means, however, I discovered that the term isn’t as illogical as it seems. It does refer to cooking for show: an activity where you can watch the chef prepare the food in front of you and then have the opportunity to eat it yourself. A performance, if you will! Though the concept is likely to have originated in televised cooking shows, it doesn’t actually refer to a “cooking show” as the term is used in English, in relation to a TV program; such shows are still known as “programas de cocina.” Rather, “show cooking” is billed as an attraction at restaurants and certain kinds of events. This kind of activity is known as as a “culinary demo/demonstration” in American English and a “cookery demonstration” in British English.

Mapping: Many psuedo-anglicisms are shortened versions of terms that English can’t actually shorten because the abbreviated form is a word that already exists, with another meaning, in English. The aformentioned case of “performance” (a shortened form of “performance art”) is one example. Others include the use of “mail” to refer to an e-mail or “web” to refer to a website. English speakers simply can’t get away with dropping the “e-” or the “site”; the word “mail” is already used to refer to postal mail, and a “web” makes us think of Charlotte the spider. The same phenomenon is behind the rise of “mapping,” or “màping,” as it’s already being used in Catalan. While ésAdir claims that this is an “Adaptació de l’anglès mapping,” it’s more accurately an abbreviation (and subsequent adaptation) of the English terms “projection mapping” or “video mapping,” since “mapping” by itself in English is typically associated with cartography and not with the visual shows that the neologism “màping” refers to. Indeed, a New York Times article explaining the concept does not once use “mapping” on its own, describing the concepts of “video mapping” and “projection” instead. Translations into English would also do better to use these terms, as the average English speaker, without a visual aid, is unlikely to know what a “mapping” in the artistic context refers to. Ironically, because so many pseudo-anglicisms are abbreviated forms of English terms, when a source text uses several pseudo-anglicisms, the target text in English (typically considered more concise than Romance languages) may end up being significantly longer than the original!

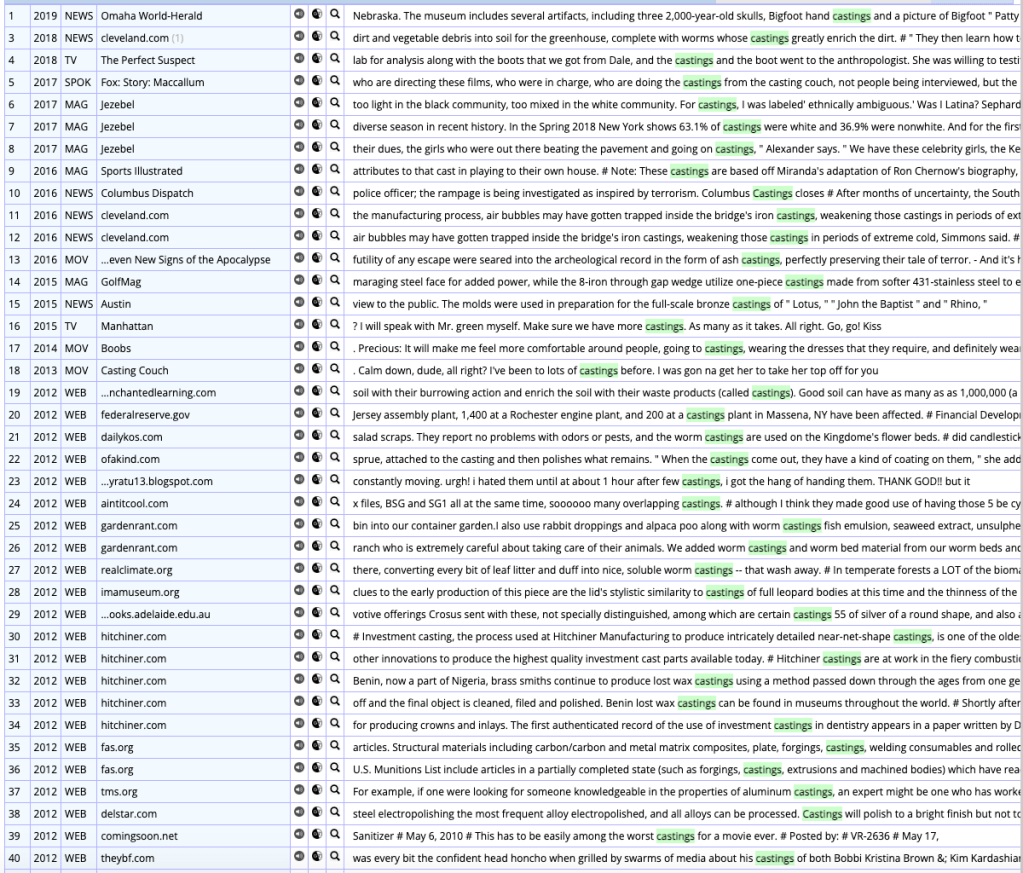

Casting: This one could be considered a partial psuedo-anglicism. When it refers to the process of choosing actors or performers for certain parts in a show or movie, the terms are used in the same way across languages: a “director de casting” is indeed a “casting director,” for example. Things get a bit more complicated when it comes to the events in which casting takes place, that is, where people try out for parts in the hopes of being picked. Before show biz people jump down my throat: yes, I know that such events can be referred to as “castings.” However, they are much more frequently referred to as either “casting calls” or “auditions.” The use of “casting” as a count noun (i.e., a noun that can be pluralized or take an indefinite article) is not common in English, as seen on the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA): there are only 357 hits for “castings,” and several of them refer to a very different kind of casting (I’m aware that there’s a genre filter on COCA, but it didn’t help much in this case).

Meanwhile, the Corpus del Español has 3622 hits for “castings,” showing that the use of the word to refer to a specific kind of event (“He tenido varios castings este mes”) is widespread in Spanish in a way it is not in English, which would likely use “auditions” in this context.

But there’s more. Not only is “casting” a count noun in Spanish, it’s gone beyond the world of show business and has come to be used for jobs that English would never associate with the word:

- El caso de la empresa que pedía a las azafatas en el casting que se quedaran en ropa interior llega a la Fiscalía

- Rob Pelinka, mánager general de la organización angelina, es quien está liderando el casting para el puesto de técnico tras la salida de Magic Johnson

In this context, “interview” or “selection/recuitment process” are possible translation solutions.

* * *

When we talk about languages “borrowing” or “loaning” words, it seems like a straightforward process, and so we assume that collecting such words back should be the most natural thing in the world. Anglicisms should be freebies for into-English translators! Why even include them in the word count? (Let’s not give cheap clients any ideas.) But just as money lent by a bank accrues interest, and just as books borrowed from the library accrue wrinkles and creases and stains as they pass from one reader to another, English speakers rarely find the words in the same condition in which they “lent” them.

And why should they be? Loanwords are not immune to the semantic processes that apply to all the vocabulary in a language, and English speakers are every bit as guilty when it comes to changing the meaning of words from other languages. A simple example: “sombrero” in Spanish can refer to a wide range of hats, while “sombrero” in English refers specifically to a certain type of hat worn in parts of Mexico and the United States. This is the same process of semantic narrowing that “performance” underwent, and the opposite phenomenon, semantic widening, is what happened to our friend “casting.” A more complex case is that of “machismo.” In English, the word is used to refer to a certain kind of toxic masculinity, and people often assume this is how it’s used in Spanish as well. In fact, in Spanish, “machismo” is essentially a synonym of “sexism.” While Merriam-Webster defines the concept as “a strong sense of masculine pride : an exaggerated masculinity” or “an exaggerated or exhilarating sense of power or strength,” machismo according to the RAE is “Actitud de prepotencia de los varones respecto de las mujeres” or “Forma de discriminación sexista caracterizada por la prevalencia del varón.” In many cases, of course, there is a great deal of overlap between toxic masculinity and sexism, but the concepts are not always equivalent:

“I think I could handle that,” Foster said, both grateful for and loathing the edge of machismo confidence in his voice.

–Foster Dade Explores the Cosmos, p. 209

The comment has to do with procuring Adderall and is not something anyone would identify as inherently “sexist.” Though there may be other contexts in which “machismo” is in fact an appropriate translation of “machismo,” in any case, it’s clear that this word is by no means a freebie for into-Spanish translators. In fact, if words that look alike in two languages but have different meanings (e.g. “carpet” and “carpeta”) are known as false friends, I would argue that “pseudo” words, the kind that purport to belong to one language when their loyalties actually lie with another, are enemies of a more insidious nature, double agents setting traps for unwitting translators. Sometimes we’ll be able to call them out, and other times we may fall for the deceit. Que sera sera.